Red Dragon (Chervenyi Sharkan) is the name of the tea from the plantation near Mukachevo. This summer, the visitors of the tea festival in Kyiv had the opportunity to taste it. For dozens of years, the unique plantation on Mount Zhornyna was left abandoned and forgotten – ever since the middle of the 20th century, when large-scale experimental tea-growing work there was over. Several later attempts by individual enthusiasts to revive the plantation were unsuccessful.

In 2019, one area of the plantation with the surviving individual tea plants was recultivated. The work was carried out by the participants of the Ukraine-Norway adaptation project for veterans and their families. Also, Maksym Malyhin, a volunteer from Kyiv who manages the plantation ever since, came to Zhornyna.

At that time, Maksym Malyhin had for several years been researching the possibilities of reviving the unique Transcarpathian tea plantation. Having first arrived there in 2013 and further on, he is meticulously studying everything about growing tea in the so-called “new tea territories”.

Tasting of Red Dragon at the festival in Kyiv. Photo by Arseniy Guzhva

Red Dragon. Photo by Maksym Malyhin

Today Maksym Malyhin is a member of the Tea Grown in Europe Association. Varosh interviewed this tea expert on the current state of the Chervona (Red) Mountain plantation, on the peculiarities of “tea business” in Transcarpathia, and on the prospects of “Transcarpathian Dragon” in general.

Maxim Malyhin

The history of the tea plantation near Mukachevo

A tea plantation on Zhornyna Mountain was experimentally established in 1949 by a group of Georgian scientists under the supervision of academician I.I. Chkhaidze. The 20-hectare plot of land allocated for the plantation was divided into 18 sectors, and several varieties of tea were sown there. The philosophy of the large-scale project was “…to fully satisfy the needs of the Soviet people for domestically-grown tea.” Previously, the tea cultivation project was successfully carried out in Georgia, so they hoped to continue this experience in Ukraine, too.

The scientists’ expectations regarding the cultivation of the Camellia sinensis tea plants in Transcarpathia came true: even without special insulation, almost half of the tea plant seedlings had survived the first winter. And as soon as in the third year, the experimental plantation yielded a harvest of over a ton of tea leaves.

“A curious fact: public resources offer barely any pictures to show the state of the tea plantation at that time. There is only one photo from the 1950s, which is now commonly used to illustrate most stories about the plantation. Today, its original is stored in the Russian archive access to which is closed,” says Maksym Malyhin. “Just a few more photos can be found in the book of Tea culture in Transcarpathia (1953) by Dr. I.I. Chkhaidze, who headed the experimental group for the plantation. In these photos, the height of the tea plants is approximately 40 centimeters. The book also mentions that in 1953, on a 1.4-hectare plantation, the yield of fresh leaves reached 1,300 kg per hectare. To date, this is the only scientific information on the yield of tea in European conditions.”

The plantation in 1953 (photo retouching and coloring by Varosh)

The project to establish the plantation came to a halt in 1953-1954: after Stalin’s death, its funding was stopped. The project was finally shut down in 1956: the tea plants on the main plantation were rooted out, and the area was planted with traditional agricultural crops.

After the experiment in growing tea in Transcarpathia was over, among the 18 plots assigned for growing tea under the forest canopy, only one plot was preserved: for many years it was looked after, in particular, by Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor of Uzhgorod National University, Vasyl Komendar.

Since the beginning of the 90s, the main area of the former plantation gradually became grown over with wild fruit trees and wild grapes, turning into impassable thickets.

In 1993, the Shiroky protected tract was created on the preserved area, and it was handed over to the Mukachevo Forestry. It is on this site that the 300 tea plants “taken under the care” of Maksym Malyhin and his associates are currently growing.

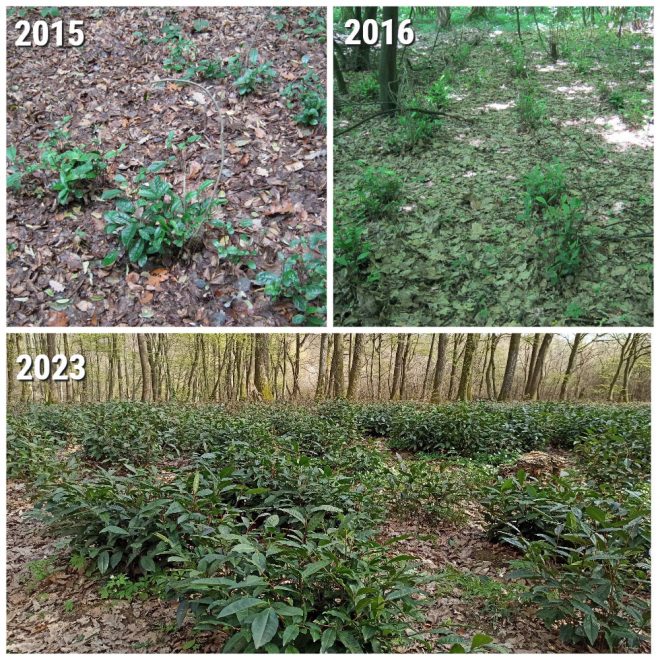

Plantation in 2013

Plantation in December 2013

According to Maksym Malyhin, the foresters’ non-interference into the ecosystem of the protected tract was “as correct as possible” regarding the tea plants preservation: “According to law, no activities can be carried out in the protected area, so as not to disturb the natural environment. However, tea plants in those areas are a part of the environment that’s no longer natural: they have been planted by humans, and are unable to survive without human care. But the camellias, despite everything, were able to survive – maybe owing to the fact that no one had conducted any specific activities there. After all, at that time we simply did not have specialists who knew the agricultural technology of tea plants, which is quite special.”

Another negative factor that threatened the tea bushes on the former plantation was… human greed. Access to the protected tract is open to everyone. So, for many years, people visiting the forest would pluck leaves and shoots from the tea plants and even dig up whole plants, apparently aiming to replant them in their own gardens.

“But it doesn’t work like that: without special knowledge and equipment, the survival rate of these plants elsewhere is about 0.5%. That is, out of 200 dug-up plants, roughly speaking, one will take root in a new place,” says Maksym Malyhin. “Tea plants require specific agricultural techniques. There are people who have been growing tea for years until they get any success. What’s more: even some botanical gardens that I know repeatedly try to grow camellias – to no effect. Camellia is a very demanding plant, not suitable for our climate: it needs to be cool, humid, and devoid of severe frosts.

Photo by Maksym Malyhin

Tea Plantation Revival: The past three years have seen excellent tea samples

After the initial visit to the plantation in 2013, Maksym Malyhin first started information campaign and promotion of the site. At the same time, he would establish connections with local enthusiasts ready to get involved in the work according to their possibilities.

In 2019, a collective group of volunteers from Kyiv and Transcarpathia carried out the reclamation of the tea plantation: they cleared an area with the remaining tea plants, which was completely overgrown with acacia and wild blackberry. The camellias’ roots were fertilized with humus, the plants got covered with agrofiber for the winter.

“For the first three years, we would systematically cover the tea plants for winter: we planned the work in advance, announced the date, and gathered a group of volunteers. The tea root growth which remained on the plantation at that time was by itself not viable enough to provide the “revival” of the tea plants, especially in our climatic conditions. In a warm climate, pruning only would be enough, but we needed additional measures,” says Maksym Malyhin. “Over time, an active core of enthusiasts was formed, which was every time joined by other interested people. Even guests from Poland and the Czech Republic came to help with the work. This was the structure of our membership until 2022. But since the volunteer core included military-reserve men, they got mobilized in the beginning of a full-scale war and are currently serving in the army.”

At the same time, according to the Mr. Malyhin, since the site is small, the work there can be done by a few people. In this case, it is not about their number, but about the fact that these people know what and how to do. This year, for example, a team of five volunteers worked on the plantation.

The first successful sample of tea from the plantation was obtained in 2020. Since that time, the quality of raw material has remained consistently high, and this, according to Mr. Malyhin, is very important, because it shows: not only can camellia sinensis be successfully grown in our conditions, but also, some really good tea can be produced from its leaves. For example, samples of fermented oolong from the plantation on Chervona Mountain, which was called Red Dragon, were sent to independent experts in Great Britain and France for evaluation in order to obtain an expert opinion. They confirmed: the quality is high, it meets the stated requirements.

This summer, Red Dragon was also presented at the Kiev Tea Festival in Kyiv. There was very little of it, though, since the tea leaves from the plantation are collected very carefully and in very small quantities. After all, the current aim is to grow and form the plants, not to collect the leaves.

Photo by Hanna Ponomarenko

“What we are doing now is the formation of skeletal branches of the tea plants, for this purpose we perform pruning every spring and weeding every summer. Whereas picking leaves is, in fact, the opposite of pruning and shaping a plant: we can be either pruning and shaping, or harvesting the tea. Therefore, very, very little tea is harvested: this year, there was under one kilogram of raw leaves, and even less in previous years. That is, now I only harvest a little to help forming the plants, so that in a few years more tea could be harvested,” explains Maksym Malyhin.

Photo by Hanna Ponomarenko

Prospects of the tea plantation and the lifespan of the “old-timer plants”

For a long time, until 1999, the tea plantation near Mukachevo was considered the northernmost one in Europe. It lost this status rather recently, when tea plantations appeared in Germany and Great Britain. However, to this day, the tea plants grown on Chervona Mountain are among the most frost-resistant varieties that can survive frosts down to -26 degrees centigrade and regenerate itself afterwards.

Despite the existing idea that the tea plantation could become a commercial object, Maksym Malyhin does not see this to happen in the near future. Generally, he doubts that the place should be commercialized at all, saying: in fact, it is scientists who should take interest in the plantation, because first and foremost it is an object for scientific research.

Red Dragon. Photo by Maksym Malyhin

“For now, from the 300 plants formed on the plantation, in the best case, up to 3 kg of finished tea can be produced. Speculating on the potential of the entire facility, remember that as of 1953, 1,300 kg of raw leaves had been harvested here, which is at least 200 kg of finished tea. For Europe, this is a very significant amount, and it would be enough for an independent project,” says Maksym Malyhin. “But the point is that this means a very long-term investment.”

According to the expert, in the conditions of Europe, depending on the nuances of the climate, it takes from 6 to 8 years to grow an adequate, adult, financially profitable plantation. And the earliest income from growing and producing tea will only be received as late as in 4 years. Now that Ukraine is going through a great war with great losses, the planning horizon is very unclear. And any drone factory will, for obvious reasons, be a higher priority than commercial tea production in the near future.

Besides, at the moment it is absolutely impossible to predict for how long the tea plants from among those planted here in 1949 will keep growing. Mr. Malyhin states that currently the world has no reliable data on the lifespan of tea plants, because commercial plantations commonly root them out after 80-100 years. Therefore, among experts, the probable lifespan of a tea plant is roughly estimated to be 100-120 years.

“So, according to calculations, the tea plants on the plantation near Mukachevo are currently 74 years old. And there is a chance that in the next few decades they will start to die naturally,” says Maksym Malyhin.

Red Dragon. Photo by Maksym Malyhin

And that is also why, he emphasizes, it is important to continue taking care of the plantation correctly: if neglected, it will most likely be impossible to restore the plantation in the future.

Although the prospects of the restored part of the tea plantation are uncertain, Maksym Malyhin believes the idea of creating a new commercial plantation, or even several at once, in Transcarpathia to be quite realistic. This is all the more possible, the expert says, given the great progress and experience in this area on the examples of Europe and the USA – the so-called “new tea regions of the world”, as well as the ongoing climate change.

Red Dragon. Photo by Arseniy Guzhva

Tеtiana Klym-Kashuba, Varosh

Translation: Olga Shpytsia

Photos taken from the page “Zhornyna” Tea Plantation – Tea is growing in Ukraine! – Tea-across-the-world on Facebook